Written by Luke Minford Chief Executive of Rouse

Leaders like Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, tell employees daily that the most valuable asset they have is their ability to move and connect more quickly than the competition. In order to achieve this, they build and connect diverse leadership teams and give them access to ever greater volumes of information so that the decisions they take are not just faster, but also more value creating than their competitors.

The pressure for change

The intellectual property services industry is simply not adapting fast enough. In an environment of increasingly rapid change, businesses are constantly playing catch-up. Externally there is ever greater emphasis on diversity of networks and on the need for speed. This is reflected in our growing understanding of how connectedness, decision making and innovation impact the organisation. Leaders like Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, tell employees daily that the most valuable asset they have is their ability to move and connect more quickly than the competition. In order to achieve this, they build and connect diverse leadership teams and give them access to ever greater volumes of information so that the decisions they take are not just faster, but also more value creating than their competitors. Internally, as new information, technologies, skills, and perspectives emerge, these organisations adapt and shape their systems, processes and structures in an attempt to keep pace.

In this environment, what is the role of the intellectual property (IP) services business (IPSB)? If we take a broad definition, an IPSB would be one that enables an enterprise to capture and exploit the value of its innovation. In this sense, and in theory, IPSB's operate at the heart of change environments, giving life to and sustaining the innovation output of clients. If we take a narrower definition, and one quite often used by lawyers, we would define an IPSB as one that helps create and deploy legal assets in order to protect and enhance the competitive position of a client. Whatever definition we use, in the context of a rapidly changing environment, the critical question remains the same; what are IPSB's themselves doing to adapt? How are they adjusting their services and business models? What of the speed and connectivity of their decision making? How are they building and connecting diverse networks of expertise to match the diverse needs of their clients?

Sadly, the answers to these questions are largely negative. The IP industry moves slowly and at a pace that lags behind its clients. It remains fragmented and painfully disconnected as an industry, where lawyers, patent attorneys, trade mark attorneys and other forms of IP specialist battle to define and protect their terrain. For the most part, IP is interpreted narrowly within the legal services industry, while the big consultancies and non-law firms who attempt to encroach on IP services remain on the outside, challenged by professional and jurisdictional barriers to entry. Business models are not being disrupted, IP services remain largely the same from firm to firm, as does the technology being deployed and the skills of most people doing the work. Attend any major IP conference and you'll be struck by how little actual change there is within the industry. To some extent, that shouldn't come as a surprise given how complex and internationally connected the IP system has become. Big systems change slowly. It is also partly due to the fact that IP is ‘housed' within the legal profession, a vocation not known for innovation. That may be because clients employ lawyers to mitigate risk, or it could be down to entrenched and age-old conventions, formalities and hierarchies that operate within the legal system, especially in the West. Whatever the cause for this resistance to change, we are left asking three critical questions: firstly, where can change come from within the IP industry? Secondly, what will that change look like? And, thirdly, when will it happen? This paper will explore these three important questions.

Organisational Life-cycles and the IP industry

"Whenever an individual or a business decides that success has been attained, progress stops." Thomas Watson, Sr (Founder, IBM).

In trying to tackle these questions, Lawrence M Miller's seminal work on organizational lifecycles is a useful reference point. Miller looks at the characteristics of organisations and the cycles or stages that they move through as they evolve. He also maps these cycles against various forms of capital wellbeing, including financial capital, innovation capital and spiritual capital. If we apply Miller's analysis to the IP industry as a whole, many (if not most) firms that we have spoken to would fall into what Miller defines as the Administrator phase of their evolution, indicated with a blue dotted line in the chart below.

According to Miller, organisations are in the Administrator phase when they no longer respond to the challenges of the external environment but seek to focus on internal solutions and protections as a means of survival. The world around the Administrator may be undergoing rapid change, but their response is to turn inwards and protect what feels secure. Some of the characteristics he uses to describe this phase include:

- Businesses are well established in their market and feel confident that clients will continue to buy products or services from them.

- There is little sense of urgency or crisis from leaders.

- A lot of time is spent focused on issues that relate to internal systems, performance and organisation.

- The number of management responsibilities being created outnumbers the number of new product or service innovations.

- Innovation is accepted as offering the same products/ services to the same customers somewhere else.

Miller notes that organisations in the Administrator phase are often at their most wealthy during this period, especially in financial terms (see graph below). He states, "during this period the financial assets are growing, brand equity is increased, and human capital is increasing with the capacity to produce. It is likely that spiritual capital is the first resource that will decline during this period, followed by the loss of innovation and then internal sociability and trust. These losses are the leading indicators of decline".

Our enquiries suggest that most IPSBs recognise that substantial changes to their external environment are taking place. However, when we look at their response, we see leaders focus internally on operational and management improvements, as well as on changes to systems and structures, rather than on externally facing innovations. Their growth strategies tend to focus on horizontal expansion aimed at selling more of the same services somewhere else. This is especially true in developed jurisdictions where IP systems have contracted since the global financial crisis. Many firms in these jurisdictions struggle to grow and in response adopt ‘more of the same' strategies in the hope that solutions will magically appear.

These growth patterns and the responses are natural. IPSBs have benefited from an enormous expansion of the IP system over the last twenty years as a result of a number of external factors, including:

- Globalisation and the critical role that IP has played in the expansion of global supply chains.

- The emerging markets growth & investment story, especially China. This in turn has driven an ‘innovation imperative as these emerging markets move up the value chain.

- The expansion of the international IP system as a result of improved harmonisation.

- An improved awareness amongst multinational corporate management teams of the value of intangible assets.

- Low interest rates and easy access to credit that has fuelled investment for much of the last decade.

Patent Application in China from 2005 – 2016, source: SIPO website

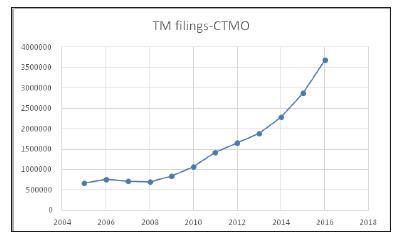

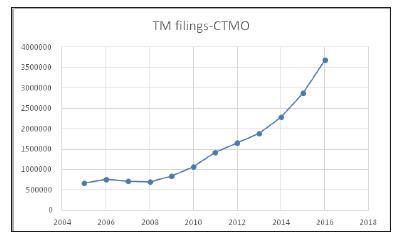

Trademark Fillings in China from 2005 – 2016, source: SIPO website

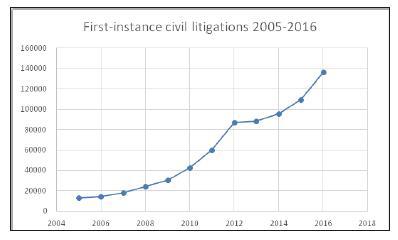

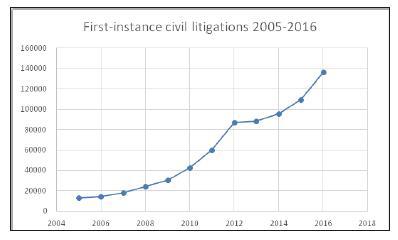

New Accepted First-instance Civil Litigations from 2005 - 2016, source: SIPO website

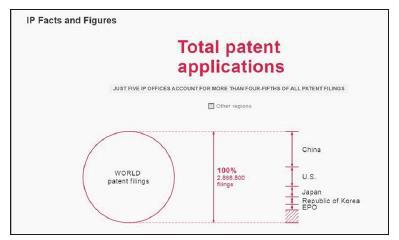

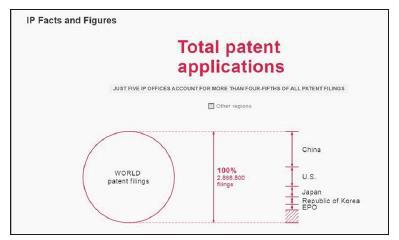

Source of image: WIPO, http://www.wipo.int/ipstats/en/charts/ ipfactsandfigures2016.html

Source of image: www.morningsideip.com/global-patent-trendsaccording- to-wipo/

As a result of these factors we have seen the emergence of IP bubbles, especially in the emerging markets. On the back of these bubbles, IPSBs have expanded just as Miller characterizes in the Build & Explore cycle. In this rapid growth, environment expansion of services tends to be reactive, with very few parts of the supply chain creating or adding value simply because there is no time or expectation to do so. This sort of sustained reactive growth can be dangerous as businesses sense no pressure to innovate, leading to the kind of inward facing behavior characterized by Miller's Administrator. For example:

- In a reactive growth scenario, IPSBs carry out known activities including investigations, raids, patent and trade mark registration, enforcement and litigation. The focus tends to be on activity outcomes and cost. However, understanding the value of this activity to the client is a much more fundamental question. At some point, the question will get asked too… how is the value of all this activity being measured? How many anti-counterfeiting raids carried out have any real impact (a key measure of value) ? What is the real value of all these people doing enforcement? What percentage of design rights or trade marks registered are creating value to the business? Of course, any effective questioning of value may result in a reduction or a change in activity, which would be disruptive and require innovation. Hence the Administrator, feeling financially secure, seeks not to question value and disrupt but to look inwards and protect.

- What about the value of connectivity? How do traditional IP systems add value in a technology connected future? Are IP systems and activities being connected fast enough for the benefit of clients? Might a technology like Blockchain enable faster, more transparent and better connected decision making on IP? Will this technology innovation create more value for the client? Again this would be a disruptive question for the IPSB to ask.

These are basic questions that go to the question of value, and the longer that IPSBs leave it to ask them, the more likely they are to protect the status quo. But as Miller notes, facing up to these questions is not easy when you've been in a reactive growth mindset, when employees are feeling the comfort of financial well-being and there is confidence in continued client demand. That's precisely when leadership is required.

Miller identifies a way out of the Administrator phase which he calls the Synergist path. This leads organisations in a direction of long term sustainable innovation and growth. The Synergist path happens when:

"transformation is brought about by leaders who recognize new challenges, acknowledge the failure to adapt to a changing landscape, and promote a new outlook, a new spirit, and new strategy"

Now is the time for IP leaders to bring about that much needed transformation. If they do not, then they will become too far removed from their clients and the external environment within which they operate. The responsibility on IP industry leaders to find the Synergist's path is real and I believe that Asia, and China particularly, is where we might see transformation taking place. Of course, many will argue otherwise and say that Asia is a region better known for infringement than innovation. They will say that China is the least likely place to lead a transformation of the IP industry. Equally, lawyers will criticise attempts to disrupt the status quo and challenge their conventions. Leaders must be prepared for these arguments. However, there are four underlying reasons why I am confident that the transformation will come from Asia, and particularly China: ?

- Firstly, the legal profession in China is relatively new, it is not yet handcuffed by its own history and conventions. There is a willingness to embrace entrepreneurialism that is missing amongst many Western legal professions.

- Secondly, the ‘innovation imperative' in China is fundamental to the next phase of its development. The pressure on Chinese leaders, both private and public, to extract positive value from the investment in innovation is critical to the grand objectives these leaders have. As the McKinsey Global Institute point out "China has the potential to meet its "innovation imperative" and to emerge as a driving force in innovation globally" but this will only happen if leaders and enterprises grasp the transformation required.

- Thirdly, China has scale and has already learnt how to convert scale to value in relation to manufacturing and e-commerce. It hasn't yet converted and leveraged its IP scale to create an innovation advantage yet, but it knows that it has to and will quickly turn its attention to that task. Xi Jinping's ‘Made in China 2025' vision provides the framework for that objective. This conversion is also being driven by the massive National Champion ecosystems built around the likes of Alibaba in Hangzhou, Huawei in Shenzhen and Baidu in Beijing.

- Fourthly, and critically, it has the ability to act with speed. The currency of speed is understood and needed in China in a way that it is not yet in other developed countries. In this, China has a distinct advantage. One of the things that foreigners who visit China from Europe comment on first is the sheer speed with which things happen. Whether consumers, entrepreneurs, business leaders, regulators or courts, whether online or offline, the speed with which the system embraces change is unparalleled. This speed is in part derived from the lack of change at a political level, but in this context, that is to China's advantage. If the IP industry in China can harness this advantage and transform, then much needed value from innovation will be derived and at much greater speed than its competitors.

What might change look like?

At a strategic level, the response to these challenges is to innovate in four ways.

1. Change of mindset: Legal rights and tools are important assets to protect innovation, but they are only one part of the solution and in some sectors a diminishing asset. Although IPSBs must not lose their ability to offer legal solutions where required, they need to embrace a much broader set of skills and capabilities. The IP industry is in need of a more diverse and a more connected network of expertise. This should include lawyers, consultants, marketers, technologists, researchers, economists, business people, engineers and more. The solutions of the future will come from the ability to integrate, connect and apply the skills of this diverse network, rather than through the narrow lens of the law.

2. A focus on value and activity: clients are under increasing pressure to explain the value of the IP activity they invest in. As markets slow, as interest rates rise, as competition in emerging markets increases, as the innovation imperative becomes real, these clients will demand solutions to this communication challenge. They will not be able to justify activity without understanding value. The IP industry must start now to properly understand value and align services and communication tools accordingly. This will be disruptive for many and the sorts of questions that must be asked include:

a. What gives our client a competitive advantage? Does this IP activity help to build that advantage? If so, how? And how do we connect the IP activity value to that advantage in a way that the business of the client understands?

b. We know that speed is now a critical currency, so how does this IP help clients move faster and at the speed they need to? How do we assess and communicate the value of speed in IP terms?

c. Are these IP services helping to reduce costs? How does cost reduction convert to value for the business? Again, what communication tools are we using?

d. Are these IP activities having the desired impact? How do we communicate the value of impact, especially in relation to enforcement of IP?

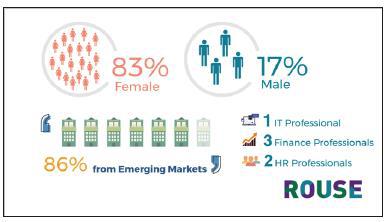

3. Leading on and connecting diversity: related to the issue of mindset is the question of diversity, not just in terms of people, but also the nature of the relationship that people can have with their organization. The IP industry in Asia has an opportunity to lead on this but it must move away from a reactive position to one that embraces diversity in its broadest sense as a solution. We recently promoted a large number of people to the position of Executive. These people came from all across our business, including fee-earners and many non-fee earners (see the below graphs to see the full extent of this diversity). What we are finding is that it is just as important to question and understand how diversity relates to the connection that people have with the organization. Diversity is one thing, but if organisations can enable a diverse group to connect with each other and with the organization in a way that maximizes the value of that diversity, then there is no solution that cannot be achieved. This isn't easy! It requires a change of mindset in relation to difficult concepts such as the meaning of ownership, the purpose of hierarchy and the value of things like status and experience. However, our experience as an Asian centred IPSB is showing that people are ready to tackle these concepts head-on.

Note: Rouse promoted 24 new equity executives following the firm's strong performance in the financial year to April 2017 including Moscow, Dubai, Bangkok, Jakarta, Hong Kong, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, London and Hanoi.

Note: The new cohort of executives has been drawn from across a wide range of different business functions, including professionals from the company's IT, finance and HR disciplines, in addition to feeearners.

4. Business model innovation: to compete over the long term, IPSBs must find alternative models that enable them to innovate more freely and operate in faster and more flexible ways. This will lead more quickly to innovations in services, pricing, recruitment, training and development, marketing and technology. It will also attract new types of clients who see their IP needs being met in ways that narrowly defined business models cannot. Instead of protecting old models and getting defensive in the face of new business model innovation, the industry must celebrate and learn from this innovation.

Innovation at Rouse - what are we doing to lead the change?

There are three strategies that we are implementing in order to drive change within our business. These are:

1. IP consultancy as the key to identifying value

We believe that IP consultancy holds the key to unlocking questions of value and not just in relation to traditional registered IP (e.g. patents, copyright and trade marks). We need to look more broadly at the entire spectrum of intangible assets, especially emerging forms of intangible assets that are necessary to compete in the new economy, such as data, algorithms and social commerce.

What differentiates consultants is that they do not use deep expertise in a given field (e.g. like a lawyer or patent attorney) to solve problems but instead apply tools and processes to identify value and measure risk. They work with clients to formulate strategies and solutions that will most effectively unlock that value and mitigate any risks. The oxygen of consultants is analysis, data and insight and so consultants need to have very broad enquiry and analysis based skills combined with a strategic mindset.

To develop consulting capability requires a separate focus. Consultancy will not grow if ‘housed' in an environment that is focused on the delivery of IP activity, especially legal activity. Reorganising the way we are structured in Rouse to facilitate the effective development of our consultancy began at the beginning of 2017 when we announced significant changes to our UK office. The UK business will now focus 100% on spearheading the development of our IP consulting services and will no longer provide downstream legal activity services. They have started from a base of highly successful global enforcement clients and are extending this base to include other types of IP consultancy, including brand and technology related consultancy. This is an exciting time for the UK and for the firm as a whole. Our London office is returning to its roots, as an innovation hub for the business, developing strategic consultancy relationships and engagements that benefit the whole of Rouse.

IP consultancy + IP activity

To some extent, consultants must be removed from downstream activity. A degree of objectivity is required if consultants are to question the value of certain activities. However, that cannot be at the expense of connectivity and speed. Often clients will want consultants to help manage the implementation of a strategy or solution, especially in emerging markets where implementation brings its own challenges and risk. At other times, consultants will be asked to pass over the implementation to specialist lawyers, or accountants, or trade mark attorneys etc. The critical point is ensuring that the organisation is optimised to allow consultancy + implementation of activity to happen in the most connected and time-effective way possible. There needs to be a degree of separation, whilst retaining the ability to implement quickly and effectively if required. Achieving that balance is about the integration and adaptation of different business models.

2. Three differentiated but integrated business models

We see three different IP service models required to deliver on the innovation needs of our clients. As noted above, our challenge is to ensure that each model has the right independent focus but at the same time is integrated and connected in such a way that clients do not lose the advantage of speed and connectivity. If these models operate in silos or are too removed from each other, then clients lose that advantage.

The three models are:

a) Consultancy - built around IP tools and processes and applied by a small and diverse team of consultants. This model is built upon a great deal of analysis, benchmarking and insight being carried out up front and often before any fees are incurred. In this sense the model is front loaded and requires a long lead time to reach profitability.

b) Legal - built around lawyers with deep expertise in a given practice. This model is well known and based largely around time based fees. In many countries law firms are regulated and so there is the added complexity of ensuring these services are delivered properly and transparently through an independent law firm structure. We do this through a network approach ensuring that law firms within the Rouse network get seamless access to the consultancy services that they and their clients need (and vice versa).

c) Portfolio & enforcement (including online enforcement) - built around technology and process capability combined with the right level of people expertise. This is largely a fixed fee based model and requires sufficient scale to ensure that gains made from technology and process improvements can be passed on to clients.

Each one of these service models delivered on their own is not that novel. There are good law firms providing IP legal services, some good consultancies doing IP work and a number of good portfolio companies providing multi-country filing and prosecution services (probably the area that has seen the most innovation and aggregation). However, very few have been able to develop these three service models successfully across an emerging markets network, and with a developed market leading in IP consultancy.

3. Connecting diversity

I mentioned above the steps that we are taking to build the most diverse Executive leadership team possible. However, below that we are actively recruiting, developing and promoting different people from more diverse backgrounds than before. We recently hired a finance consultant into a practice team to help them better understand the financial impact of certain IP activities on the clients business. We have hired into our consultancy technology specialists, science & innovation policy experts and project managers all with a view to expanding our understanding of value. This diversity of recruitment would not have been supported or encouraged under our old ‘law firm' mindset.

As mentioned above, it is just as important to connect this diversity to itself and to the organization if it is to create a real advantage. Rouse has always had a relatively horizontal structure but as we bring in and develop a more diverse group of leaders there is then greater emphasis on the need to promote and support collaboration and connectedness. We do that by reinforcing three things. Firstly, by reinforcing the right culture and behavior in the way that we reward and incentivize people. Secondly, by making sure that our structure does not get too vertical and that people are always encouraged to speak to and connect with whomever they need, no matter how senior. And thirdly, by investing in communication technology that allows people to connect effectively across offices.

Conclusion

There are more questions in this paper than there are answers. Asking questions is where change starts. The IP industry in Asia, and particularly China, can lead this discussion and drive forward the much needed change but it requires a critical mass of leaders within the IP community to do so. If the IP industry is to keep pace with what is happening around it, then this discussion needs to be about value in the broadest sense of the word. That requires looking beyond narrow definitions of IP at the wider question of intangible asset value. It requires challenging traditional systems and ways of working in order to see value in speed, connectivity and business model innovation. And it requires a much wider understanding of the value of diversity. These are the currencies of the future and IPSBs must start investing in them now if they are to find the path of the Synergist.